Protocol Design

slipstream acts as a TCP proxy server, tunneling the streaming data between a client and a server over DNS, supporting the use of different DNS resolvers in parallel. A major aspect of slipstream is the use of QUIC1 multipath2 as the transport protocol.

Protocol Stack

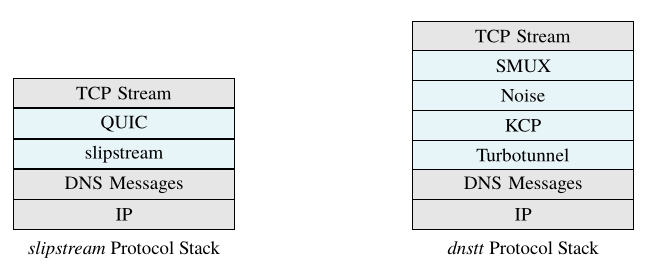

Following dnstt’s approach outlined in TurboTunnel3, we decouple the encoding layer from the session and reliability layers. Compared to dnstt, QUIC combines the KCP, SMUX, and Noise layers into a single protocol, as shown below. slipstream itself does not implement any reliability based on DNS message status codes, keeping reliability management completely within QUIC. A DNS message with a failure response code does not necessarily mean that the message was not delivered to the DNS tunneling server.

Protocol stack comparison between slipstream and dnstt.

QUIC implementations are abundant, allowing us to pick and choose an implementation that fits the pull interface proposed in TurboTunnel. The main selection criteria for a QUIC implementation is support for a pull interface and the multipath QUIC extension. The latter deemed especially challenging as this RFC is going through many changes in each version of the proposal. As of writing, the only libraries supporting multipath QUIC are mp-quic, TQUIC (draft v5), XQUIC (draft v10), and picoquic (draft v11). We’ve found picoquic to be the simplest implementation to work with, supporting the latest proposals and providing a pull interface for sending and receiving packets.

Reduced Header Overhead

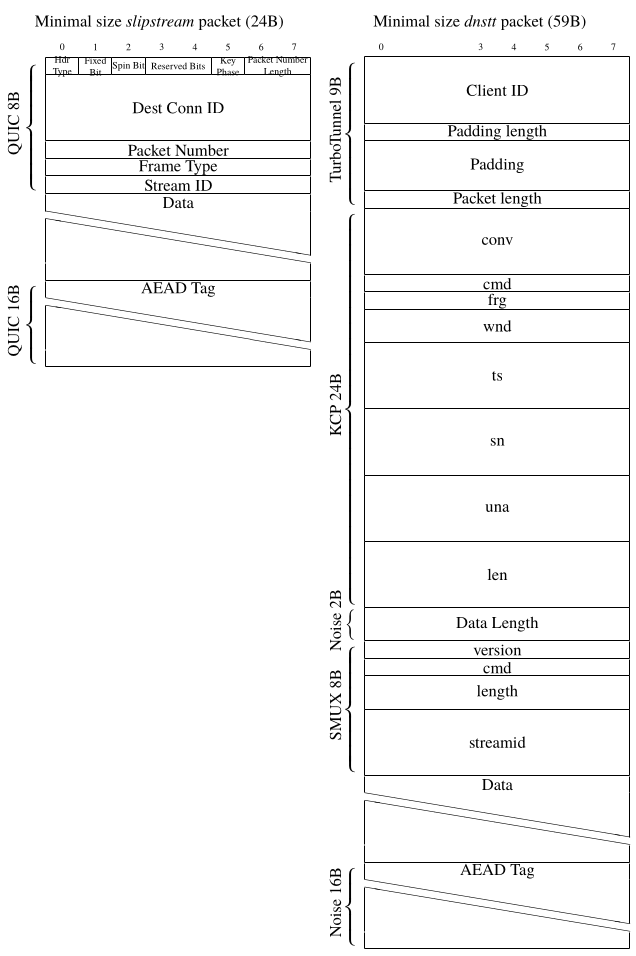

QUIC optimizes the header size. Compared to dnstt, this allows slipstream to reduce the header overhead from 59 bytes to 24 bytes (see the detailed bytefield diagram below). QUIC uses variable-length integers to encode certain fields, allowing for more efficient encoding of small numbers. Using a single protocol also ensures that there is no redundancy in the header, which is an issue as found in the repeated length fields in the combination of TurboTunnel, KCP, SMUX, and Noise in dnstt. For encoding and decoding QUIC packets in the DNS message, slipstream follows dnstt and encodes data into the domain name using base32 and puts raw data in TXT response records. slipstream does not add any additional headers or fields on top of QUIC. While dnstt adds a packet length marker, we rely on QUIC to add packet length markers when needed (e.g. when coallescing multiple packets into a single DNS message). For dnstt’s random padding cache-breaking solution, we also rely on QUIC to use unique packet IDs (see QUIC1 section 12.3.). QUIC frames to be retransmitted are wrapped in new QUIC packets (see QUIC1 section 13.2.1.), which ensures that retransmissions are unique too, preventing the need for additional random padding as seen in dnstt. Finally, QUIC already tracks a connection ID in the header, so we do not need to introduce an additional connection ID field in the header either.

Comparison of slipstream and dnstt packet formats.

Another consideration is that QUIC expects the Initial packets to have a minimum size of 1200 bytes to prevent amplification attacks. Since DNS messages are so limited in size, we have to reduce this limit on both the client and the server side depending on the size of the domain name used. Of course, we could still integrate response rate-limiting on unauthenticated client IDs. We could also further delay the server response until a certain number of initial frames have been received, for example based on the expected crypto message size.

Congestion Control

Achieving high performance in DNS tunneling requires careful management of query rates to maximize throughput while avoiding rate limits imposed by DNS resolvers. In addition, with larger RTTs, DNS tunnels suffer from low performance4, showing the importance of a good congestion control algorithm. Since the bandwidth of a single stream is mostly based on the RTT and window size (i.e. related to bandwidth-delay-product), managing the window size is crucial. While QUIC supports congestion control algorithms, we need to make several changes:

-

On the client side, we need to choose a congestion control algorithm. As a DNS resolver hits its rate-limit, it drops or responds to the client without forwarding the message to the server. In addition, as a DNS tunneling server is processing a high number of DNS requests, it may experience congestion and slow down the response time. Thus, we choose a congestion control algorithm that balances latency and loss signals (DCUBIC in picoquic).

-

On the server side, we disable the congestion control algorithm entirely, and remove the congestion window. This allows the server to always respond to incoming DNS queries, maximizing its use of limited opportunities to send responses. We assume that if a DNS query can reach the server, it must be able to reach back too, as the DNS resolver’s rate-limit may be the primary bottleneck in the network path.

-

While QUIC attempts to prevent an “infinite feedback loop of acknowledgments” (see QUIC1 section 13.2.1.) on non-ACK-eliciting frames by delaying acknowledgments up to

max_ack_delay, the server may not be able to respond to the client’s acknowledgments in time if no further DNS query arrives. We ensure that this loss signal is not considered by the QUIC congestion control algorithm as to prevent unnecessary lowering of the congestion window. -

As a DNS resolver may use multiple threads, DNS messages may not be delivered in order. In preliminary testing, we observed that DNS messages may be received out of order by hundreds of packets. To ensure that this signal does not influence the congestion control algorithm, we ignore out-of-order loss signals and instead rely solely on RACK signals5.

Connection IDs and Multipath

QUIC relies on the connection ID to track individual connections, rather than a source address. The QUIC multipath extension2 in addition proposes to use multiple network paths simultaneously using this connection ID, effectively allowing to aggregate the individual bandwidth limits of multiple paths. In the case of DNS tunneling, each path corresponds to a different DNS resolver, each with its own network conditions and rate limit.

Although QUIC primarily uses a connection ID for tracking individual connections, it relies on source addresses for path management (i.e. migration). Since DNS packets may arrive at the DNS tunneling server from any source address, we hard-code a dummy address into every received packet before passing it to QUIC. As a result, several QUIC features should be manually disabled. For example, “A PATH_RESPONSE frame MUST be sent on the network path where the PATH_CHALLENGE frame was received.” (see QUIC1 section 8.2.2.) ensures that a path is valid in both directions, while our DNS tunnel server is only ever aware of a single path. And, “An endpoint can migrate a connection to a new local address by sending packets containing non-probing frames from that address.” (see QUIC1 section 9.2.) implies that the server would be aware if the client changes its source address, while our DNS tunnel server only ever receives a dummy address (instead of constantly changing DNS resolver addresses).

Polling

The polling mechanism in slipstream builds upon dnstt’s strategy of replying to every server reply with a poll message. To ensure that poll messages are considered as part of QUIC’s congestion control counters in slipstream, we introduce a new QUIC frame type for polling. The poll frame is a frame with size 0, such that the only space used is the frame type. To prevent an infinitely growing number of poll messages pinging back-and-forth, QUIC should consider poll frames as non-ACK-eliciting frames, allowing QUIC to ignore responding to poll messages when the server has no data to send, in turn preventing new poll messages from being sent at the client. If possible, we replace an outgoing poll message with a real frame that contains data. This ensures that when the server is sending data, the poll messages won’t take precedence over the client’s outgoing data frames. We enable the QUIC keep-alive option to ensure that even when there is no data between the client and the server, the server may still initiate data transmission by responding to a keep-alive packet. This keep-alive period largely influences the server-to-client latency while idle and the number of packets sent while idle and should be manually tuned based on the user’s requirements.

Encryption

QUIC provides built-in encryption, mutual authentication, and integrity checks. This means that we do not need to implement a custom solution, reducing the complexity of the tunneling protocol.

Timings

DNS resolvers may keep track of round-trip-times of authoritative nameservers and drop or retransmit packets for responses that arrive too late. For example, Unbound DNS resolver keeps track of ping, variance, and RTT for its timeout management6. Thus, we ensure that the DNS tunnel server responds as soon as possible to a DNS query and does not buffer any messages for responding to later.

Performant Encoding

In high performance tunneling where the bottleneck becomes the tunnel performance, the speed of encoding and decoding is crucial. There is a trade-off between the encoding and decoding speed and the features of the DNS encoding library. To support future use of different record types in the encoding, we choose to use a DNS library allowing for encoding and decoding of arbitrary DNS records. While initially using the c-ares library, but it was found to be decreasing the performance of the tunnel. We settled on the SPCDNS library, which keeps the processing time of encoding and decoding to a minimum. Although the library is very bare-bones, it is quite sufficient for our use-case.

Similarly, the performance of base32 encoding is crucial. In slipstream, we use the implementation of lua-resty-base-encoding, which has proven to be one of the fastest implementations available.

Socket loop

For tunneling purposes, we need to poll on 2 sockets: one for the TCP stream and one for the DNS messages. When DNS messages arrive, we decode the message and pass it to the QUIC library using picoquic_incoming_packet_ex. To improve the performance, we allow multiple packets to be received before attempting to respond. For sending retransmissions, acknowledgments, or new data on the TCP stream, we poll on the QUIC library using picoquic_prepare_next_packet_ex.

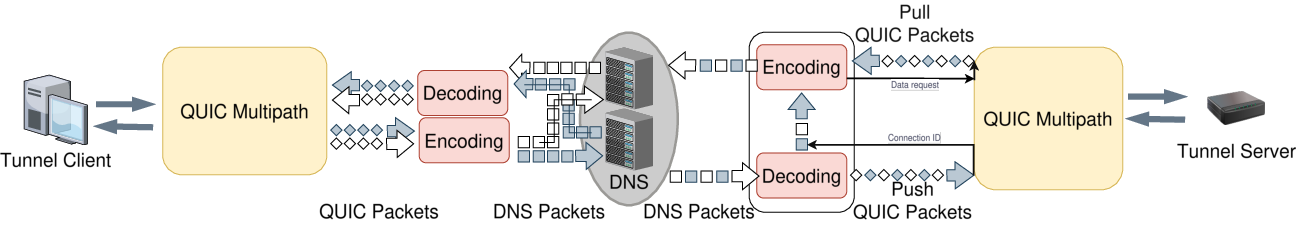

In the server side, we buffer the multiple incoming DNS messages in a FIFO queue, such that we can respond to them in order. Before passing on the QUIC packet, we spoof the source address of the incoming DNS message to a dummy address, and annotate the DNS message with the original source address and connection ID. Once ready to send a response, we pull the next QUIC packet on the related connection, encode it in the DNS response, and send it over the UDP socket to the correct destination address.

For sending data, picoquic requires the program to keep track of active and inactive streams, only requesting data from the stream when it is active. This is a bit cumbersome, as our tunnel constantly needs to poll the TCP socket in a separate thread and wake up the main picoquic when there is data to send.

The socket loop's data flow.

-

QUIC: A UDP-Based Multiplexed and Secure Transport (RFC 9000) ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6

-

Multipath Extension for QUIC (draft-ietf-quic-multipath-14) ↩ ↩2

-

David Fifield. Turbo Tunnel, a good way to design censorship circumvention protocols. FOCI 2020. ↩

-

Lucas Nussbaum, Pierre Neyron and Olivier Richard. On Robust Covert Channels Inside DNS. 24th IFIP International Security Conference. 2009. ↩